Christine De Pizan and The City of Ladies

To celebrate Women's Day, Folia Magazine decided to offer a brief in-depth analysis of one of the most important female figures of medieval culture: Christine de Pizan.

Christine was born in Venice in 1365. Her father Tommaso was a professor of medicine and astrology at the University of Bologna and was originally from that area. However, four years after his daughter’s birth, he was called to the court of the king of France and had to move to Paris with his family. The young Christine thus grows up within a refined and intellectually stimulating environment, immersed in the countless volumes of the Royal Library founded by the king himself, Charles V, and composing poems from an early age.

At 15, Christine marries Étienne de Castel, notary and secretary of Charles V. They have three children, one of whom sadly dies at a young age. Christine's life will really change about ten years later, when, left a widow and an orphan after her father’s death, she will find herself having to provide for the family all by herself. About this moment, Christine writes:

“I found I had a strong and brave heart - which astonished me- but I felt that I had become a real man”.

This transformation into a “real man” allows Christine to take on a role traditionally linked to the male figure: becoming the head of a writing shop, she can dedicate herself to her passion for poems, writing ballads of love in particular. These capture the attention of several patrons, whose commissions allow Christine to financially support her family.

Christine's notoriety grows considerably during the first few years of the 15th century, when she takes part in a literary debate about one of the most famous and appreciated compositions of that time, Jean de Meun's Roman de la Rose. Christine's main criticism of the work concerned the way the female figure is dealt with, as she is only seen as a seductress. It is exactly this desire to represent women in a way that is closer to reality that pushes Christine to write what will prove to be her main literary composition: the Book of the City of Ladies.

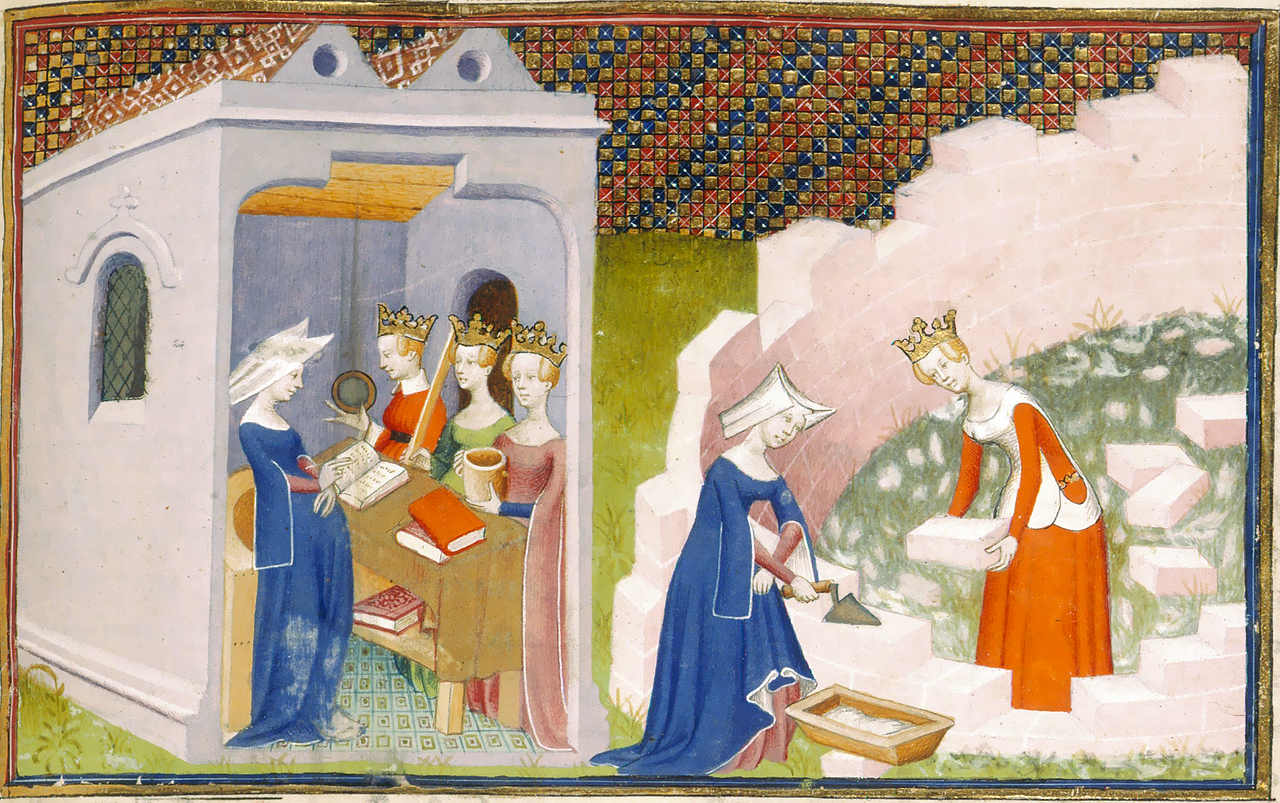

Her work was conceived as a direct response to the simplistic vision of women, illustrating, as Boccaccio didbefore her in his De mulieribus claris, the lives of some of the most prominent female figures (historical, literary and religious) and their contributions. Each woman therefore constitutes a “brick” of the symbolic City Christine is trying to build with the help of the three Virtues of Reason, Righteousness and Justice. Hereeach Lady (a term that the writer uses to describe women of noble spirit rather than highborn) can be appreciated and protected beyond any stereotype. The sequel to the Book, the Treasure of the City of Ladies, focuses instead on the importance of female education of all levels, seen by Christine as the only means to include women in the cultural scene.

After finishing the Book and the Treasure of the City of Ladies, Christine continues to write prolifically, developing a certain interest in historical themes. In 1418, after the occupation of Paris by the British and the Burgundians and shortly after her fifties, Christine retired to a convent and put her pen aside for eleven years. Only in 1429, about a year before she died, Christine will finally write her latest work, inspired, not surprisingly, by a female figure: Joan of Arc, who came that year to “represent” France in the Hundred Years War. Full of joy for having personally witnessed the rise of a woman, a Maiden, to heroine of an entire state, Christine opens her Ditie de Jehanne d’Arc with the following words:

“I, Christine, who had been crying for eleven years locked in an abbey, now for the first time laugh, laugh with joy”.

Folia Magazine wishes all of you the happiest of Holidays with this delicate,…

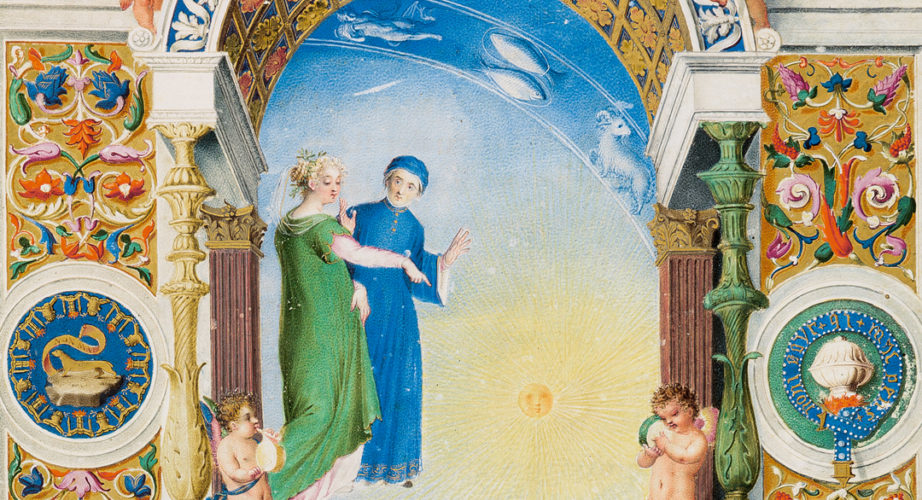

The cover page of the Paradiso displays an architectural structure that is complex…

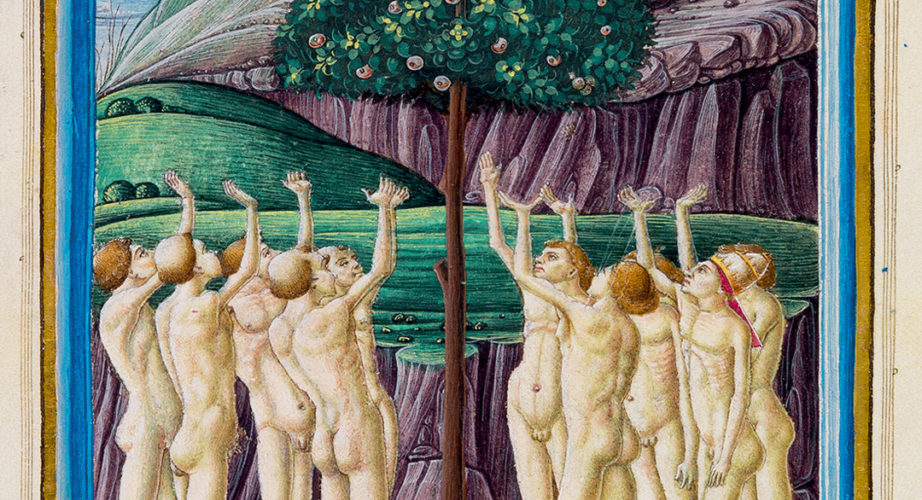

As the three poets continue their journey through Purgatory, they reach the sixth…