Medieval Antisemitism: the origins on the Judenstern

On January 27, 1945, the Soviet Red Army entered Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. With the opening of the lager gates - made sadly famous by the writing that then became its symbol, Arbeit macht frei - the whole world finally realized the horrors of Hitler’s "Final Solution". To remember the Holocaust and reaffirm its role of warning against the dangers of hatred, racism, and prejudice, in 2005 the United Nations established the International Memorial Day.

Folia Magazine, therefore, proposes today an in-depth study aimed at showing how some aspects that we are used to consider as limited to that historical period have much older roots. This is the case, for example, of the well-known Judenstern: the yellow star of David that Jews were forced to wear under the Nazi regime.

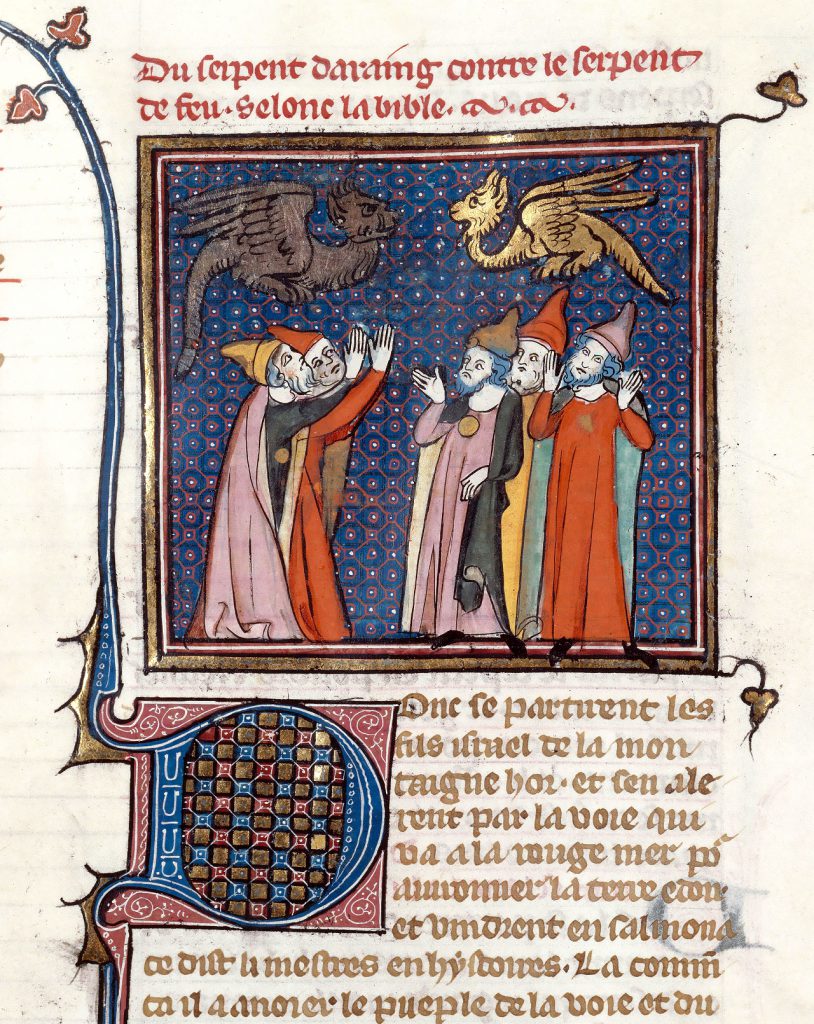

If today the religious persecution of Jews throughout history is widely known, we cannot probably say the same about the ways in which this persecution was carried out. The obligation to be immediately distinguishable from the rest of the population, in fact, was perhaps the main form of discrimination and persecution imposed on Jews since the 8th and 9th centuries. It is during this period that we can find the first mention of a dress code for the Jewish population in Islamic territories: under the caliphate of Omar II (717–720) every non-Muslim minority (dhimmī) was ordered to wear a distinguishing sign of their religious faith (called giyār). This order was reaffirmed in the following years: in Sicily, for example, the Saracen governor forced Christians to wear a piece of cloth in the shape of a pig on their clothes, while Jews were assigned a donkey. They were also forced to wear a high cone-shaped headdress and a yellow belt. These signs, however, were not necessarily intended as derogatory or punitive. Their official purpose, in fact, was to reaffirm the status of dhimmī of the religious minority, assuring it certain rights and protection.

After the Crusades, the custom of imposing a dress code on religious minorities soon spread all over Europe. The definitive regulation took place on November 11, 1215, on the occasion of the Fourth Lateran Council. On this date, Pope Innocent III ordered that Jews and Muslims should wear specific clothing in order to be immediately distinguishable from the "good Christians", thus limiting the risk of relationships between individuals belonging to different religious communities. This decree, not specifying the nature nor the type of clothing to be worn, left much freedom to regulate these distinctive signs. If in Italy the symbol mainly took the form of a circular yellow patch (with the exception of the Republic of Venice, where the chosen color was red), Spanish Jews were instead identified by red. In these territories, however, this badge was made only occasionally mandatory.

In France, on the contrary, an edict of Louis IX (later canonized as Saint Louis IX King of France) officially imposed the use of the rouelle (a wheel or disk shaped patch, usually yellow or white, but sometimes also red or white) as early as 1269. The rouelle constituted a double imposition for Jews: not only they were forced to wear it by law, but each Jew also had to pay a large sum of money to be able to buy it first, in addition to an annual fee to be allowed to keep owning it.

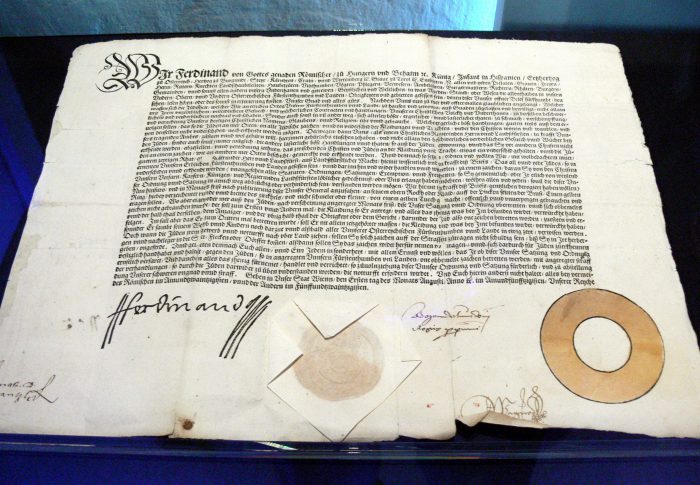

At first, in Germany and in the territories of the Holy Roman Empire the garment imposed on Jews was the characteristic pointed hat called pileum cornutum. In 1279, the Church council that took place in Budapest decided to oblige Jews to wear a badge similar to the French rouelle, known in German as the Gelber Ring (“golden ring”). This ordinance was first imposed in Augsburg in 1434 and later extended to all of Germany in 1530. The use of the Gelber Ring was also introduced in Austria starting from August 1551, when Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg declared it mandatory through an official edict.

The papal edict of 1215, however, was accepted even more promptly in England. Already in 1217, in fact, King Henry III ordered that Jews should wear distinguishing marks on their chests. Finally, in 1275, Edward I specified the color, shape, and size of this badge: each Jew was therefore obliged, from the age of seven, to wear a piece of yellow felt. The shape was that of the tables of the Law raised by Moses on Mount Sinai, considered a symbol of the Old Testament.

The use of these badges started to fade with the beginning of the Enlightenment period - until it disappeared almost completely after the French Revolution and its winds of progress spreading throughout Europe.

Folia Magazine wishes all of you the happiest of Holidays with this delicate,…

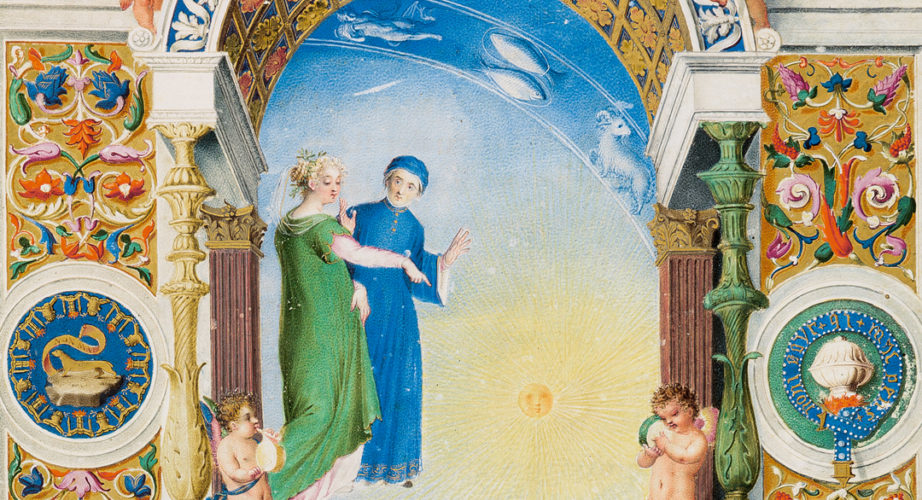

The cover page of the Paradiso displays an architectural structure that is complex…

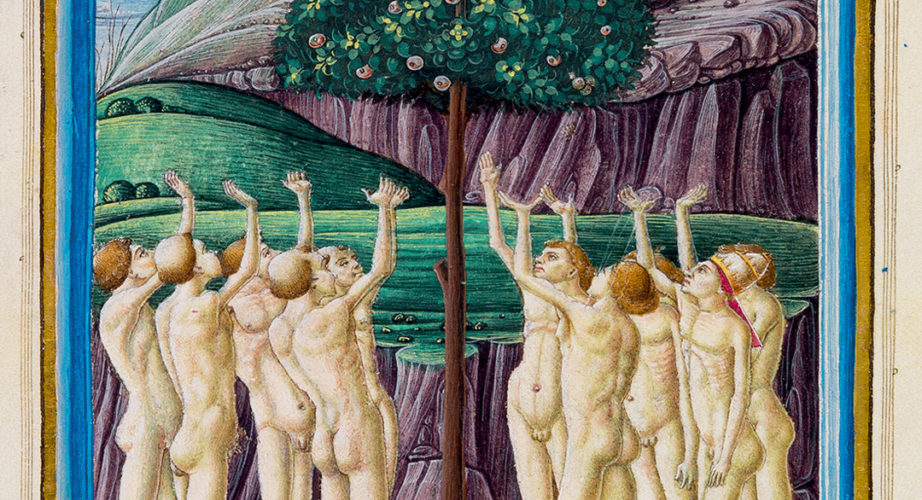

As the three poets continue their journey through Purgatory, they reach the sixth…