Medusa

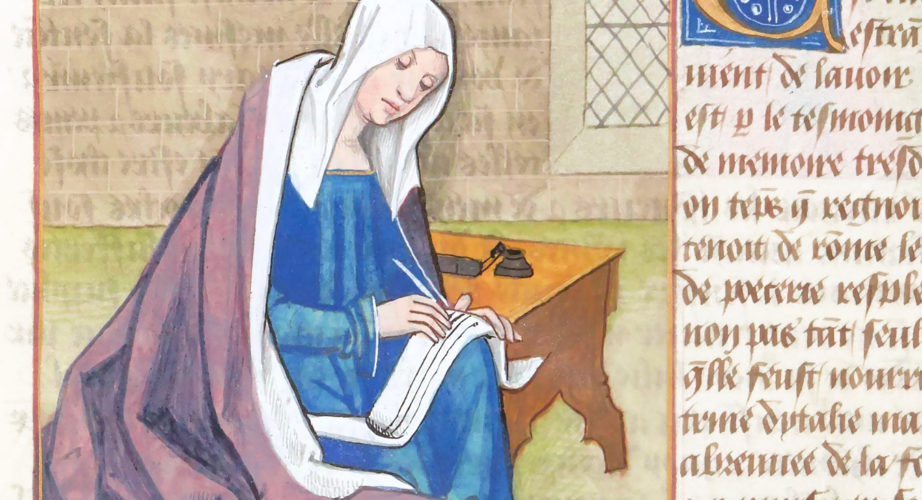

Time for a new appointment with our Women's Wednesday! You may not have guessed it by the illumination above, but our guest this time is Medusa, the famous Gorgon with snakes in place of her hair. Why is her depiction in the De Mulieribus Claris so different from what we are used to?

Most myths, as you probably know, describe Medusa as a monster who would petrify whoever made eye-contact with her; some state that she originally was no more than a normal maiden who was later turned into a monster by Athena, who was either jealous of her beauty or offended by the fact that Poseidon had raped the girl in one of the goddess' temples. Either way, Medusa was eventually killed by Perseus, who then fled on the winged horse Pegasus, born from Medusa's blood.

Boccaccio, however, doesn't believe any of this: according to him, in fact, the myth is but an embellished version of a more "mortal" story. His version of the myth is as follows: Medusa was the daughter and heiress of Phorcys, king of some islands in the Atlantic. She was blessed with incredible beauty, long gold hair and a magnetic gaze that would make men instantly fall in love with her. In addition to this, her skills as a ruler eventually made her the richest among kings and queens in the West. Made famous by these gifts, her name traveled all across Europe, eventually reaching a young Greek named Perseus. Fascinated by both beauty and gold, the man set sail to Medusa's reign on a ship carrying a flag depicting a winged horse; he then seduced the queen (or even kidnapped her), took a great quantity of gold, and went back home.

Boccaccio identifies the source of Medusa's troubles (and legacy) in gold itself, saying that "to possess gold means misfortune" ("Infelix auri possessio est").

“Medusa”, illumination from the manuscript “Cas des nobles hommes et femmes”, ms. Français 12420, f. 31r, 15h century, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Paris.

Historically and mythologically speaking, being in a powerful position (and perhaps also a…

The time has finally come for the very first Women’s Wednesday of 2021!…

Welcome back to another Women’s Wednesday! Our weekly Mulier Clara, much like Sappho…