(Not) The End of the World as We Know It

The official Folia Magazine Instagram account has reached the milestone of 1000 followers! To celebrate, we decided to look into the origin of the Italian saying "Mille e non più mille" ("A thousand and a thousand no more"), notoriously said to date back to the "Millennium Madness" around 1000 AD. But is it true? Were our ancestors really afraid the world would end at the turn of the Millennium? Are there any records of it? What we discovered was even more interesting than what we anticipated.

As one may suspect would be the case for Medieval Europe, the 1000 AD "crisis" had a lot to deal with religion. It is said, in fact, to have originated from an interpretation of the Apocalypse (or Book of Revelation):

And I saw an angel coming down out of heaven, having the key to the Abyss and holding in his hand a great chain.He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil, or Satan, and bound him for a thousand years. He threw him into the Abyss, and locked and sealed it over him, to keep him from deceiving the nations anymore until the thousand years were ended. After that, he must be set free for a short time.

When the thousand years are over, Satan will be released from his prison.

(Book of Revelation, 20:1-3, 20:7)

According to the interpretation of these verses, Satan was to be unleashed into the world one-thousand years after Christ; the world thus panicked, then nothing happened, then everyone went back to their own lives. Not much different from the Mayan Apocalypse in 2012 or the Y2K scare the world experienced about 20 years ago, right?

Except, it is. You see, many debate that there is actually little to no evidence that this Millennium Madness ever happened: despite several records of the year in question, in fact, none seem to mention any cases of mass panic like the ones we often picture. Many modern historians (with the prime example being George Lincoln Burr at the beginning of the 20th century) agree on the interpretation that most people were actually not even aware of the supposed End of the World, being the Bible still only available in Latin and only to the higher classes; there also seems to be an issue with the date itself, since Europe was still very fragmented in the choice of its calendars.

Other historians, moreover, go as far as saying that orthodox medieval Christianity would not have permitted an apocalyptic interpretation of the Book of Revelation, as this was outwardly prohibited in his doctrine by Augustine himself. In short, this school of thought denies any form of fear around that year in particular and states that the so-called "Terrors of the year 1000" were no more than a creation by the Romantic historians of the mid-nineteenth century.

But what about those historians who do believe that 1000 AD was, in fact, a time of turmoil?

More recent historians (like professor Richard Landes) focused their studies in researching and discussing the possibility that Millennial Madness was, in truth, more than the panicked frenzy one may expect. As Landes states in one of his papers, it can be argued that both the Romantic and the "denying" views on 1000 AD fault in automatically assuming that the End of the World would be awaited in fear alone; for many believers, in fact, the End was also a greatly-anticipated spark of hope.

The Apocalypse would coincide with the Last Judgement, meaning that the poor and the meek would inherit the Earth and their oppressors would finally be punished for their sins. Despite this being the very core of Jesus' famous Sermon of the Mount, it goes without saying that this idea carried a strong political meaning: it was very well in the interest of the ruling groups (holding both secular and temporal power, meaning both the noble and the Church) to oppose such a subversive view. In light of this, then, the lack of written, in-depth evidence should come to no surprise, being almost all written word in the hands of the Church or the powerful; moreover, as we were saying, there might have been little to no "paralysis" in itself, meaning also not much to report on annals and the like.

Reinforcing the importance of "apocalyptic hope", Landes makes another point by bringing a few examples that may prove people were actually more affected by the turning of the Millennium than what was previously believed: movements such as the so-called "Peace of God”, with its idea of redemption after a period of disaster and penance, as well as the rise in pilgrimages to the Holy Land or in the veneration of saints and their relics, may in fact have their origin in the wait for an end - or, on the contrary, a new era.

You can read Landes' full paper on 1000 AD here.

Folia Magazine wishes all of you the happiest of Holidays with this delicate,…

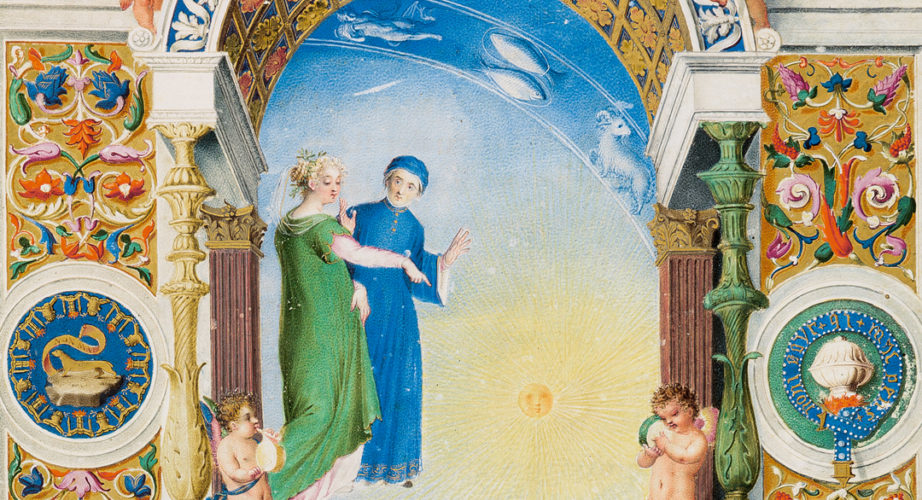

The cover page of the Paradiso displays an architectural structure that is complex…

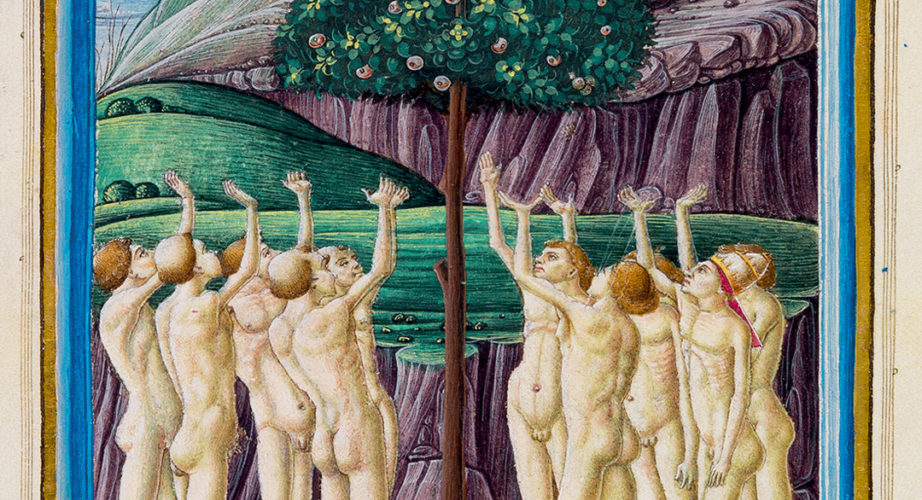

As the three poets continue their journey through Purgatory, they reach the sixth…